Why Do White People Want To Say The N-Word So Badly?

Source: Karl Gehring / Getty

It’s wild that in 2021 we still must explain when and in what context white people can use the N-word. While for some it may seem like a complicated discussion worthy of debate, the answer is simple:

Not as a part of a discussion. Not as an example. Never.

And yet debates persist, even among journalists and media personalities, about whether there are conditions where people can use it. But the focus on whether white people can use the word often ignores broader issues within workplaces, illustrating much deeper issues.

I just checked The NYT Alumni Group on Facebook, and the first thing I saw was a “When is it acceptable to use the N-word?” poll. https://t.co/INpcqqfN83

— Lil Uzi Hurt

(@lostblackboy) February 22, 2021

The real question is why are white people so focused on being able to say a word that has always been an offensive term leveled at Black people. A common misbelief around the word is that it was used to mean simply someone who was ignorant, so that could warrant broader use of the term.

With close to 200 years of experience defining words, an expanded entry on the Merriam-Webster Dictionary website debunked the claim that the word has other uses.

“Its offensiveness is not new—dictionaries have been noting it for more than 150 years—but it has grown more pronounced with the passage of time,” read the entry. “The word now ranks as almost certainly the most offensive and inflammatory racial slur in English, a term expressive of hatred and bigotry.”

The entry continues on to explain that despite alleged other uses or origins, the word was and continues to be a derogatory term for Black people.

“There has never been a definition like ‘an ignorant person’ for this word in any subsequent dictionary published by this company,” concluded the entry. “We do not know the source of those beliefs, but they are not accurate.”

The N-word first appeared in Merriam-Webster in 1864 and included a notation that it was used in a depreciating or derisive manner. Given the well-settled historical use and context for the N-word, why are journalists and media personalities fixated on being able to use this word in any capacity?

Slate recently suspended Mike Pesca, host of the Slate podcast, “The Gist.” As initially reported by Defector, Pesca shifted a conversation in the company Slack from a discussion about a now-former New York Times reporter’s resignation after coming under fire for using the N-word. Accounts from several staff members, and screenshots obtained by Defector, show that Pesca steered the conversation to his belief that there are situations that permit the word’s use.

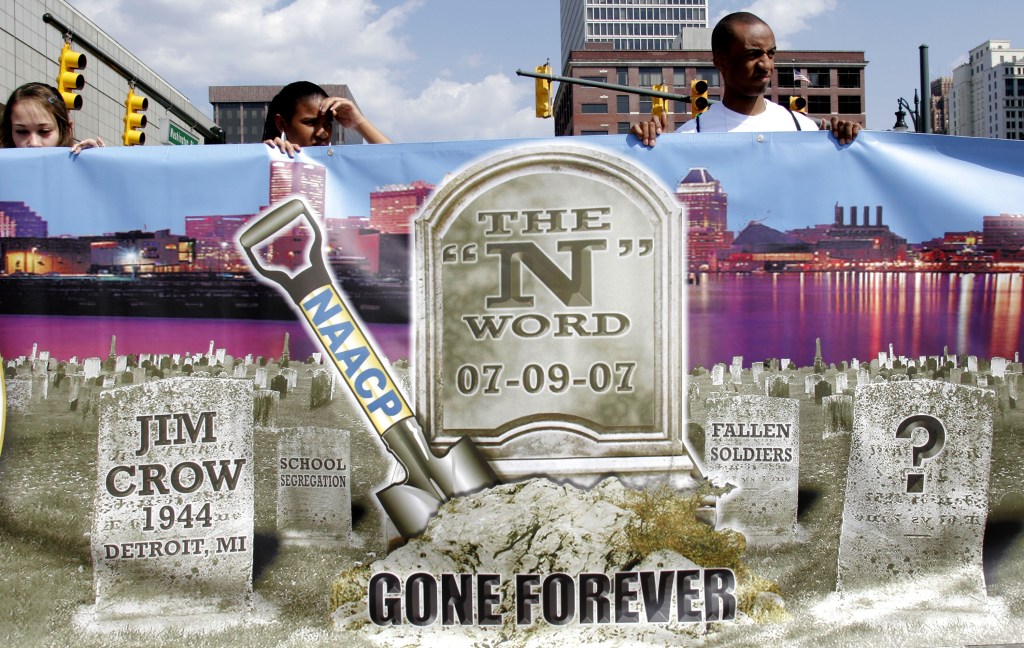

The NAACP held a mock funeral to bury the N-word in Detroit in 2007. | Source: Photo by Bill Pugliano/Getty Images / Getty

Pesca even tried to hide behind an article written by a Black writer exploring whether white people can ever use the word. In a 2019 article for the Atlantic, John McWhorter focused on the case of Laurie Sheck, a professor who received backlash for her use of the N-word during a class discussion about the documentary, “I Am Not Your Negro.” McWhorter pointed out that James Baldwin had actually said, “I am not your nigger.” Sheck used the word when she asked her class why the title substituted the word “negro.”

But McWhorter’s argument for why Sheck’s use should be acceptable (for this writer it was unnecessary and sensational) does not absolve Pesca’s documented history of trying to use the word or force conversations about why he should be permitted to use it in certain circumstances.

It’s not for Pesca, or any white person, to decide their use is proper. Also, Black people using the word in self-determined expression, as did Baldwin in 1963, does not give Pesca, Sheck or anyone else the right to repeat it.

Arguably, part of the reason the word is so taboo has to do with deeper issues of power and discrimination. Forcing discussions about the use of the word, instead of confronting actual issues of power and hostility, undermines people’s experiences in workplaces and academia alike.

It’s about the power and entitlement of the person fixated on saying a word they have been told is off-limits. Also, conversations about whether white people can use the N-word are more about feelings of entitlement and whataboutism.

And this isn’t about whether the version of the word used ends in -er or -a. Or whether rappers say it, too. That’s another conversation entirely. But for the record: No, white people also can’t say it when singing the lyrics to a song.

Having journalists and others who decide coverage and narrative framings stuck on using any racial epithet is only a small part of a larger conversation about how the media is centered in whiteness and fixated on fictional harms while not addressing real challenges.

Not being allowed to use the N-word as a white person is not an injustice. Anyone claiming there is room for debate about when white or other non-Black people can use the word is not really interested in discourse.

They just want to protect a sense of entitlement and access.

Anoa Changa is a movement journalist and retired attorney based in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow Anoa on Instagram and Twitter @thewaywithanoa.

SEE ALSO:

Michigan Official Defends N-Word Against Black Lives Matter: ‘It Is Not Racism’

Niece Suggests Trump Has Routinely Used The N-Word And Anti-Semitic Slurs

[ione_media_gallery id=”3924027″ overlay=”true”]