The Stokes Brothers And The Promise Of Black Men

Once, there was a pair of brothers. They grew up poor, raised in the Outhwaite Homes housing projects in Cleveland, Ohio, by their widowed mother. When the older brother joined the Army, the younger dropped out of school and went to work at a factory making aircraft parts to help fight World War II and put food on the table for a year until he was old enough to follow his brother into the service.

They never had much of anything. But they worked hard, they never gave up and they never stopped believing in what was possible for themselves, their community and our nation.

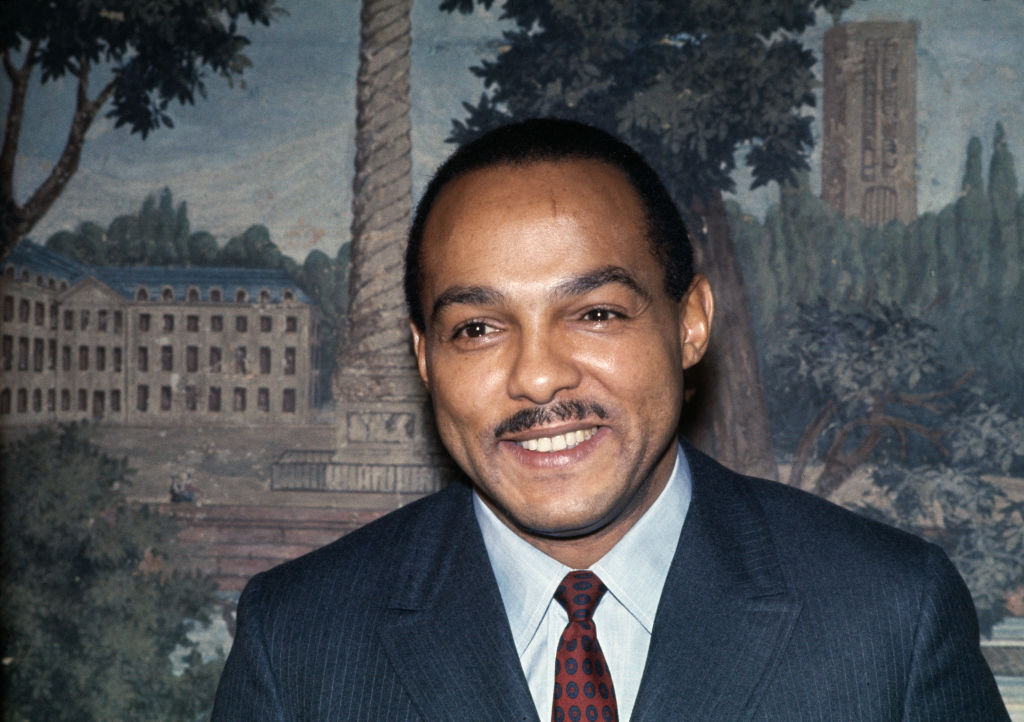

Source: Bettmann / Getty

That faith sustained them through the war, college and law school. It drove them to serve every chance they had, to help make sure that those who came behind them had the kinds of opportunities they never dreamt of. It drove the oldest brother to fight Ohio’s “Stop and Frisk” law in the United States Supreme Court and, on November 7, 1967, it drove the younger brother, Carl Stokes, to become the first Black Mayor of Cleveland and the first Black Mayor of any major city in America.

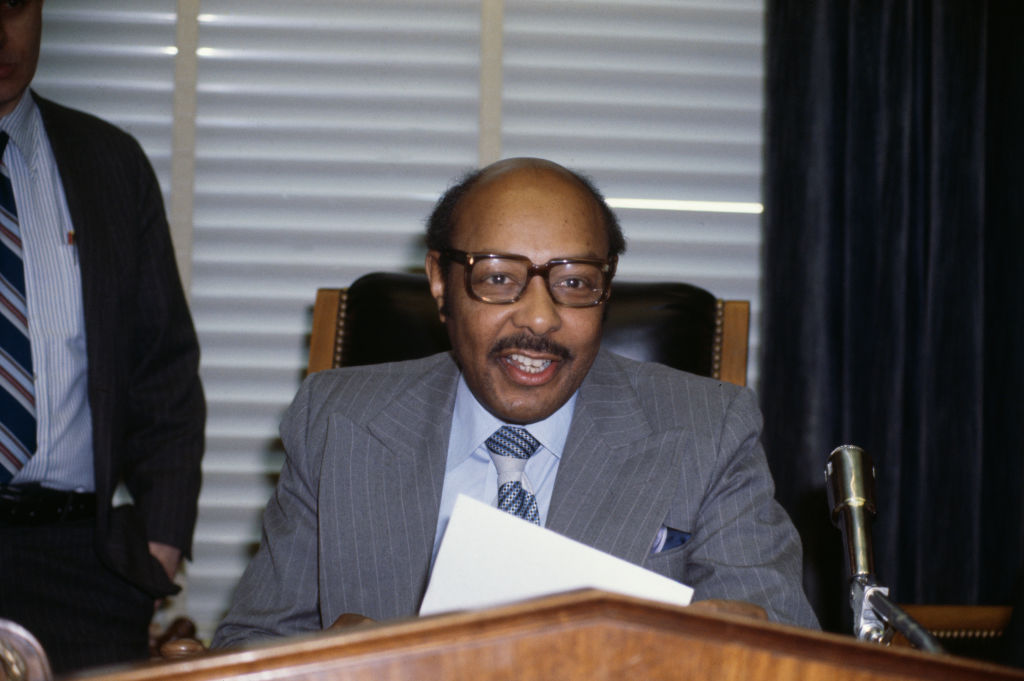

Source: Bettmann / Getty

Two years later, Louis Stokes would follow his younger brother into the political spotlight when he was elected to Congress where, among other things, he was a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus.

“The thrust of our elections was that many black people around America who had formerly been unrepresented, now felt that the nine black members of the House owed them the obligation of also affording them representation in the House,” Rep. Stokes said in 1971. “In addition to representing our individual districts, we had to assume the onerous burden of acting as congressman-at-large for unrepresented people around America.”

Now, there are a lot of reasons to remember Carl and Louis Stokes from their long public service to the examples of leadership they both left behind. Personally, I feel a specific kinship because, as fellow members of Kappa Alpha Psi, the Stokes brothers are fraternity brothers of mine.

But today, as we look towards Martin Luther King Day, I remember the Stokes brothers for their unshakable faith and unflinching commitment not just to who we are…but who we can be.

You see, like most of us, the Stokes brothers had a lot of reasons to give up. As Black children born poor in the mid-1920s, they already had a hard row to hoe. Then their father died stealing away the family’s chief breadwinner right before the great depression. Every time it looked like rock bottom, some new hardship blew the floor from beneath them and new obstacles rose to make it even harder.

So they had a lot of reasons to stop believing. But, for some reason, they never did. They never turned to righteous anger or violence against a system that didn’t care. They never turned their back on their family, their community or each other even though it might have made things a little easier. They never went for the easy money or the surface satisfaction that hid a deeper hardship. They kept pushing no matter what.

They kept the faith, not in a system that disregarded them at every turn when it wasn’t actively abusing them and suppressing their rights as Americans, but in the principle that says we stand strongest when we stand together.

As Dr. King said, “All men are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be.”

So now it’s up to us to learn from the examples of Louis and Carl Stokes and, on this MLK Day, rededicate ourselves to weaving that garment of destiny.

As Black men, we need more brothers like the Brothers Stokes whether we’re volunteering as mentors and community activists, activating our fraternities like my beloved Kappa Alpha Psi to rebuild our communities or simply engaging each other to make sure our voices are heard loud and clear at the ballot box on Election Day.

Let me be clear, I know how tough it is. From cancer rates to the income gap, Black men are facing serious challenges, many of which we’ve been struggling with since the Stokes brothers’ day.

Black men in the United States have the lowest life expectancy and suffer worse health than any other racial group in America. Black students are nearly four times as likely to be suspended from school as white students for the same behavior and, while Black boys make up only 18% of male preschool enrollment, they receive 41% of male preschool suspensions.

The same “Stop and Frisk” Louis Stokes fought at the Supreme Court is making a comeback today. Mayor Stokes made headlines by opening City Hall jobs to women and minorities with the kind of DEI initiative MAGA disciples are fighting to shut down across America.

Black Americans are five times more likely to be incarcerated than whites and one in every three Black boys born today can expect to spend at least part of their lives in prison. That’s the same kind of disparity Mayor Stokes was fighting when he tried to reform Cleveland police back in the 60s. So let’s not pretend these are new problems.

The truth is that it was downright deadly to be a Black man in America back then just as it is today. But it doesn’t have to be that way. There’s a legacy of strong Black men like Dr. King and the Stokes Brothers all across America and, if we want change, then we have to embrace that legacy and rise to this moment.

Dr. King used to say that “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is: ‘What are you doing for others?’”

It’s up to us to answer that question.

Once, there was a pair of brothers and, together, they not only rewrote a destiny that seemed set in stone but taught us to rewrite our own.

They taught us what brotherhood was all about and showed us that if we believe in each other, if we stand together and we never stop pushing forward, the sky isn’t the limit…it’s just the beginning.

Antjuan Seawright is a Democratic political strategist, founder and CEO of Blueprint Strategy LLC and a senior visiting fellow at Third Way. Follow him on X, formerly known as Twitter @antjuansea.

SEE ALSO:

The Black History Of Altadena And Pasadena

The Brothers Of Pine Oak: The Mysterious Disappearance Of A Slave Family Searching For Freedom