Tennessee Man Once Sentenced to Mandatory Life Sentence Under ‘Three Strikes’ Law Freed from Prison After Black Attorney, Kim Kardashian Advocated for His Release

It’s a story of second chances centered on a judge, a reformer and a prisoner.

Chris Young spent 3,694 days behind bars after he was arrested for dealing drugs. He was fated to rot in federal prison for the rest of his life. But Young never lost hope that he would somehow be freed one day. That faith in his freedom came to fruition on Jan. 20 when Young’s sentence was commuted.

Now he wants to be a bridge between the streets that once consumed him and the world of technology where he envisions his future.

“It’s life after life,” Young told Atlanta Black Star during a recent interview. “So I’m trying to live my best life, as they say. And I’ve been enjoying every moment.”

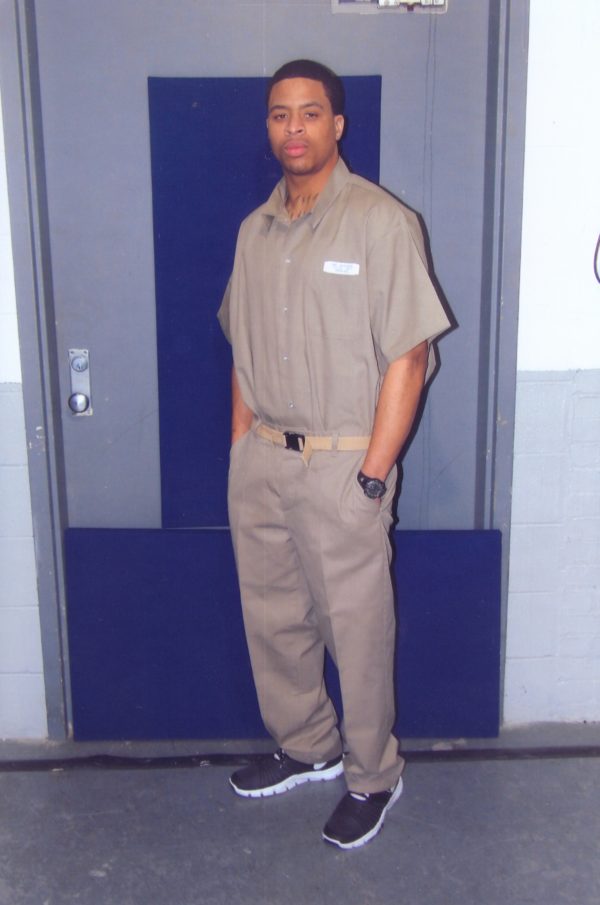

The Freed Prisoner

It’s been about four weeks since Young walked out of a federal prison in Texas, tasting freedom for the first time in more than a decade.

He was sentenced to two life sentences without the possibility of parole after he was convicted as part of a federal drug conspiracy in 2014. But the curtain on his second act rose when it seemed all hope was lost.

Former President Donald Trump granted Young clemency as one of his last acts before leaving the Oval Office on Jan. 20. It was a part of a round of executive pardons and commutations in the final hours of Trump’s presidency that included figures like rappers Lil Wayne and Kodak Black, Death Row Records co-founder Michael “Harry O” Harris and Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief political strategist.

“I literally was pronounced to go sit in a building in die,” Young said. “So to be back free, I’m coming back from the grave. Legally, I was sent to go die. I wasn’t supposed to leave the custody of the [Bureau of Prisons] until I was pronounced deceased. So that’s powerful to be free.”

Young’s release is four years in the making for Brittany Barnett, the criminal justice attorney who fought to make his dream a reality. She began petitioning for Young’s sentence to be commuted in 2017.

“Words really fail to express just the pure joy,” Barnett told Atlanta Black Star. “When I took the case and not having a clue of how it was going to happen, but I just knew that it would happen. And to be here now and to know that he is about to touch the world in a way that I’ve witnessed and seen, I just can’t wait for other people to witness and see it as well.”

Young, now 32, grew up in Clarksville, Tennessee, and was exposed to drugs and gangs at at an early age. His mother fell into drug addiction and he fell into the dope game. Young was one of nearly 40 people arrested in 2010 on federal charges as part of a drug conspiracy ring. He was charged with drug trafficking for dealing a kilo and a half of cocaine.

Young saw himself as a bit player in the operation and felt like he would receive a relatively light sentence. He was one of the few defendants who opted not to take a plea deal.

But Young had two minor drug convictions from his late teens. The amount of drugs from those prior convictions weighed “less than three pennies,” according to Barnett. But they exposed Young to a much harsher punishment.

Barnett said federal prosecutors enhanced the penalties against Young after he refused to plead out, invoking the federal “three-strikes” laws. That raised the stakes dramatically. It meant Young’s third conviction came with an automatic life sentence, a remnant of the bygone drug laws of the crack era.

“It was more time, if not equivalent, to what Charles Manson, the Unabomber, and the Golden State Killer Joseph DeAngelo got,” Young said. “These people have murdered and raped 10’s, 20’s, sometimes even close to 100 people. And I got the same sentence.”

An Agent of Reform

Brittany Barnett is a former corporate lawyer turned criminal reform advocate who now does pro bono work representing people condemned to die in prison for federal drug crimes. Changing the system of mass incarceration and erasing racial disparities in sentencing is a deeply personal agenda that hits close to home for her. When Barnett was 22, her mother was sentenced to eight years in prison for violating probation after failing a series of drug tests.

Barnett helped seven clients get pardons under former president Barack Obama’s clemency initiative. In 2019, she helped litigate for the release of 17 more nonviolent drug offenders as part of the 90 Days of Freedom Campaign, which was bankrolled by Kim Kardashian West.

She co-founded the Buried Alive Project, a coalition of attorneys that works to free prisoners sentenced under outdated federal drug policies. She started the initiative with Sharanda Jones, the first prisoner she worked to get released. Jones was a first-time offender sentenced to a life sentence for a non-violent drug conviction.

She began working on Young’s case in spring 2017 after a journalist who profiled him introduced the two.

“I take on cases that I believe come to me divinely,” Barnett said. “And because of that, I put everything, all of me into them. It’s emotionally taxing because it’s literally a place, a time where I have people’s very lives in my hands. And it’s something that I don’t take lightly.”

Young spent little over seven years in federal custody. He served his first years in a maximum-security penitentiary in McCreary County, Kentucky, before being transferred to a medical facility in Lexington, Kentucky, for surgery. Young was later shipped off to a U.S. prison in Beaumont, Texas, that prisoners referred to as “Bloody Beaumont,” where he served out the final two years of his sentence.

Young said he devoted his time to reading, working out and teaching himself coding skills. Naturally fascinated with science and technology, he said he kept up with the fast-moving world of technology while behind bars by reading magazines like Fortune, Forbes, MIT Technology Review, and the Robb Report.

“I let myself think outside the box, that’s what took me outside of that box,” he said. “It allowed me to explore the world and live vicariously through these great authors.”

A Judge’s Remorse

Kevin Sharp, the federal judge who presided over Young’s case, had the misfortune of ordering the mandatory life sentences. It was a ruling that Sharp disagreed with and one that tormented him for years.

In 2017, Sharp stepped down from his lifetime appointment to the U.S. District Court, citing the lack of discretion he was allowed in mandatory sentences for cases like Young’s. Days after resigning from his federal judgeship to join a civil rights law firm in Nashville, Sharp explained to The Tennessean why Young’s sentencing ate away at him.

“If there was any way I could have not given him life in prison I would have done it,” a tearful Sharp said while discussing the case with the newspaper. “What they did was wrong, they deserved some time in prison, but not life.”

After reading Sharp’s comments in the news article, Barnett contacted the former judge and asked for his help on Young’s case.

She and Sharp met and discussed a strategy to get Young released. They decided to lobby for presidential clemency and enlisted the help of Kardashian West, who successfully advocated for Alice Johnson’s release.

Johnson was sentenced to life in federal prison following a 1997 drug conspiracy conviction. Trump commuted her sentence in June 2018 at Kardashian West’s urging and stepped in to pardon Johnson fully on Aug. 28, 2020, one day after she spoke at the Republican National Convention and thanked Trump for giving her a second chance.

In September 2018, Sharp and Barnett attended a White House meeting with the reality star where they lobbied on Young’s behalf. The meeting went well, but it all seemed to be in vain until Trump’s final day in office, when he commuted the sentence.

A White House statement acknowledged Sharp’s assessment that Young’s life sentence was “not appropriate in any way, shape, or form,” and made note of his support from federal prosecutors and a bevy of criminal reform advocates.

“Mr. Young has made productive use of his time in prison by taking courses and learning coding skills,” it stated. “He also has maintained a spotless disciplinary record. Mr. Young’s many supporters describe him as an intelligent, positive person who takes full responsibility for his actions and who lacked a meaningful first chance in life due to what another federal judge called an ‘undeniably tragic childhood.’”

Sharp was the first person Young met at the airport when he landed in Clarksville, Tennessee.

“I knew it was not something that he wanted to do,” Young told CNN of the judge’ ruling. “He wasn’t choosing for me to have two life sentences. America and its judicial systems chose that. … It’s called a mandatory minimum and it means exactly that — it is mandatory. So I knew he had no choice.”

Barnett was able to get Young’s sentence reduced to 14 years in September. But she also condemned the federal mandates that had him facing life for so many years. She called into question the Department of Justice being so heavily involved in reviewing clemency petitions from prisoners that the agency prosecutes, calling it a conflict of interest. Barnett believes the petitions should be routed through a bipartisan third-party advisory council that includes input from defense attorneys, prosecutors, and the formerly incarcerated. She also advocates for the legalization of cannabis and progressive criminal reforms that are retroactive.

“We have to really be honest with ourselves as a country, and be honest with ourselves to face the past,” she said. “To know that our drug laws in this country are bleeding with racial injustice. And once we’re able to acknowledge that first, then let’s talk about how we can reimagine what the system looks like, as it relates to the utter failure of the war on drugs.”

The First Step Act, which Trump signed into law in December 2018, eased the three-strikes laws and shortened the mandatory minimums for nonviolent drug offenses to 25 years. Barnett noted that while the law changed, it’s not retroactive.

“So it’s not reaching back to help people like Chris Young,” she said. “And that’s very problematic that people are serving life sentences today under yesterday’s drug laws.”

As for Young, he says he’s working to get a book about his life published. He’s also striving to build a career in the STEM fields with the skills he taught himself.

He said he made the conscious effort to keep his mind free, using his release from prison as the North Star to keep him grounded.

“I always believed in my freedom,” he said. “But faith without works is dead. I didn’t just go in there and sit on my hands. You have to play some type of part, and I was fortunate enough to impress the right people with my work ethic, my ambition and my dedication.”