Statue Of Freedom Fighter Robert Smalls Set To Be Built In Beaufort, South Carolina

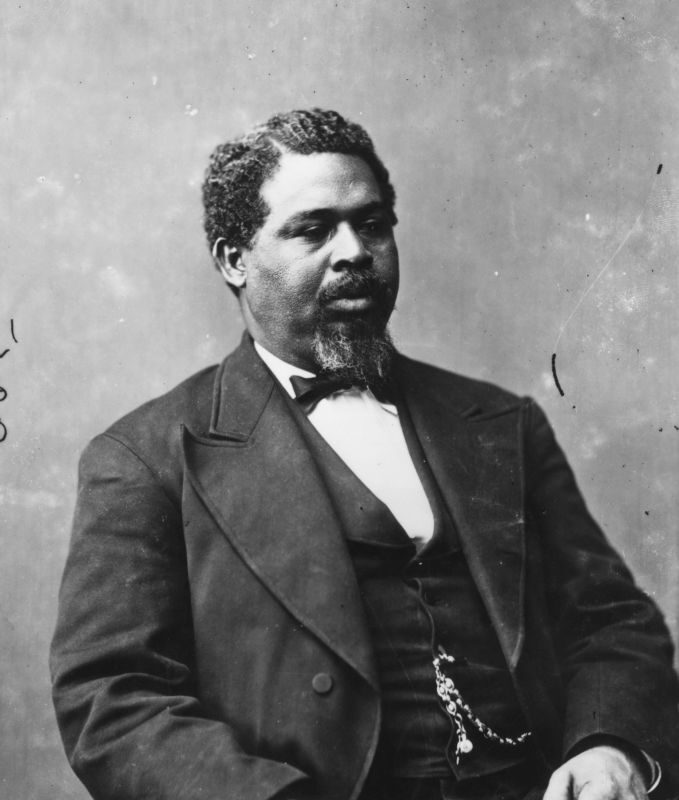

Robert Smalls – Source: MPI / Getty

South Carolina is set to make history soon when a statue of the remarkable Robert Smalls is erected in Beaufort, a quaint city located on Port Royal Island.

Thanks to the efforts of the Robert Smalls Monument Commission, established by Act 183 of the 2024 South Carolina Legislature, a monument honoring the freedom fighter is set to be built in the former Confederate state, which once had more slaves than white colonizers and settlers. He is the first Black person to have such a distinction.

The South Carolina Department of Administration website notes that committee members are currently working on the monument’s design, and according to the Associated Press, the commission has until Jan. 15 to finalize its vision. The monument to Smalls will be placed on the State House grounds. The Commission is tasked with raising private funds and may also receive gifts and grants to support the initiative.

Rep. Jermaine Johnson Sr. of Richland County expressed his excitement about the statue, looking forward to sharing Smalls’ remarkable legacy and achievements with his children. “The man has done so many great things, it’s just a travesty he has not been honored until now. Heck, it’s also a travesty there isn’t some big Hollywood movie out there about his life,” the Democrat told the Associated Press.

The Planter – Source: Interim Archives / Getty

From enslaved pilot to liberating hero

Born into slavery on April 5, 1839, in Beaufort, South Carolina, Robert Smalls faced tremendous challenges from the start. The son of an enslaved woman, Lydia Polite, and possibly his enslaver, John McKee, Smalls was forced into a life of bondage, PBS noted. At just 12 years old, he was sent to Charleston as a hired laborer, where he gained valuable maritime skills working on ships in the harbor.

His life took a dramatic turn during the Civil War when he was forced to pilot the CSS Planter, a Confederate steamboat transporting arms, cotton, and ammunition. On May 13, 1862, yearning for freedom and equality, Smalls, who loved the sea and had worked hard as a hired-out laborer on Charleston’s docks, also learned how to pilot large vessels.

He used his knowledge to commandeer the Confederate ship, break through one of their blockades, and get the vessel–and the slaves who were aboard it–including his wife and children– safely to the Union Army, the University of South Carolina notes.

Smalls would eventually become the first Black pilot in the U.S. Navy and then the first Black captain of what was now the USS Planter. In that role, he valiantly led the fight in 17 Civil War battles.

A warrior on the sea, a warrior in the legislature

Following the war, Smalls returned to Beaufort, where he was elected to the state legislature, and then the United States House of Representatives, serving from 1874 to 1879 and again from 1881 to 1887. During a tumultuous period known as the “Southern Redemption,” which sought to strip political power from Black Southerners and Republicans, Smalls navigated the political landscape with resilience, briefly losing his seat in 1878 but regaining it shortly thereafter.

In Congress, Smalls was instrumental in securing funding for improvements to the Port Royal Harbor and advocated for the rights of Black Americans, striving for full citizenship and equality, the University of South Carolina highlighted. He opposed segregation in the military and public spaces, fighting against the emerging Jim Crow laws. It was he who wrote the state’s first legislation that provided all the children of his state with free, compulsory education.

Smalls retired from Congress in 1887 but not from service. For two decades, he was Beauford’s Collector of Customs, a powerful government position critical to the movement of international products in its region. Local white residents strongly opposed Smalls in that role, but as he had earlier in life, his intelligence and savvy ensured he prevailed.

An incredible final bow

During his military service, Smalls made a point to return to Beaufort whenever possible. By January 1864, he had used the $1,500 prize money from his capture of the Planter to purchase the mansion of the McKees, the family that he was once enslaved by, PBS noted.

Smalls acquired the property at a tax auction for assets belonging to white residents who’d fled after the city fell to Union forces in 1861. It was an incredible turn of events: a man once enslaved on a plantation became not only a war hero, legislator, and national figure, but a man who transformed the seat of his hell into the seat of Black America’s hope.

SEE ALSO:

Juneteenth: The Civil War Was A Black Reconstruction