‘Seems Pretty Suspect’: A Pioneering Black Judge Was Set to Have a Federal Building Named In His Honor, Until a 1999 Article Resurfaced and GOP Members Blocked the Measure

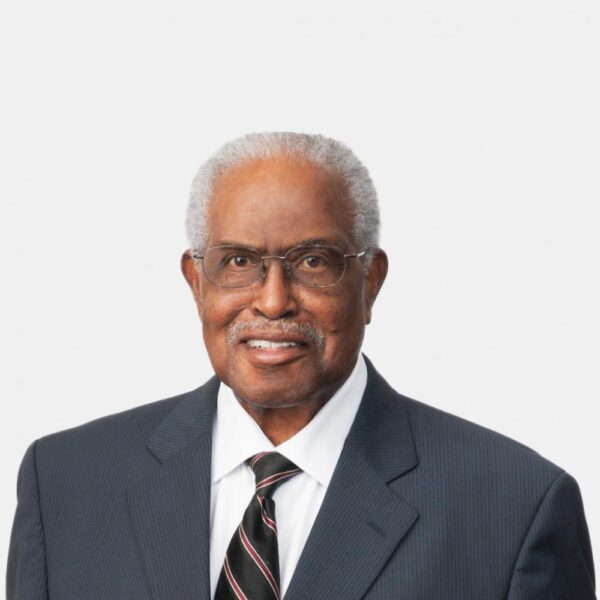

A bill to name a federal building after the first Black judge on the Florida Supreme Court was expected to breeze through the U.S. House last month after being unanimously approved in the Senate, but a Georgia Republican quickly turned a flock of GOP members against Justice Joseph W. Hatchett, ultimately killing the bill.

The measure sponsored by Florida’s two Republican senators cleared the Senate in December. A House version on the bill was introduced in July by Florida Democrat Rep. Al Lawson Jr. of Florida and co-sponsored by 25 other representatives from the state. Sixteen of them are Republicans.

However, many of them voted against the Senate bill late last month, after Rep. Andrew Clyde of Georgia unearthed a newspaper article from 1999.

“He voted against student-led school prayer in Duval County in 1999,” Clyde, a Baptist deacon, said. “I don’t agree with that. That’s it. I just let the Republicans know that information on the House floor. I have no idea if they knew that or not.”

One of the bill’s sponsors, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, said Hatchett “was a remarkable public servant with a significant tenure on the bench.”

Hatchett died in April 2021, at 88, nearly 22 years after retiring as the first Black man appointed to the federal appeals court in the Deep South. In 1975, Florida Gov. Reubin Askew appointed Hatchett as the first Black Florida Supreme Court justice.

As a trailblazer, Hatchett reportedly could not stay in the hotel where the Florida bar exam was being administered when he took it in 1959, because of segregation.

Naming a federal building after Hatchett should have been easy. Similar bills usually pass with partisan concurrence without debate or a recorded vote. However, the measure failed to meet the two-thirds threshold required to clear the second chamber on March 30. The House voted 238-187, with 89 percent of Republicans opposed.

According to The New York Times, one of Clyde’s staffers found The Associated Press article from 1999, about Hatchett’s decision to override a lower court’s ruling to allow student-approved prayers at graduation ceremonies. Hatchett contended that the public school policy violates constitutional protections of freedom of religion.

Hatchett had cited the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in Lee v. Weisman that prayers during a graduation ceremony prayer constituted “a state-sponsored and state-directed religious exercise.” The Supreme Court also ruled in Engel v. Vitale in 1962, that school prayer violated the Constitution’s Establishment Clause.

Still, Clyde, who has a track record of voting against race-based legislation since taking office in January 2021, took issue with the ruling.

Clyde voted against a bill that makes lynching a federal hate crime and another recognizing Juneteenth as a federal holiday. Clyde’s most notable deed so far has been comparing the U.S. Capitol Riot to a “normal tourist visit” and opposing a resolution to give the Congressional Gold Medal to police officers who responded to the attack on Jan. 6, 2021.

Clyde told The New York Times that race had nothing to do with his opposition to the measure.

“We’re one race — the human race,” he said. “It has everything to do with the decision he made.”

Democrat Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz of Florida believes Clyde’s motive goes deeper than religion or extremism, however.

“If the standard that we use is one ruling out of thousands, then what else could we conclude but that they are not willing to name a courthouse after a Black person,” Schultz said. “It seems pretty suspect.”

Other Democrats said the bill’s progression is an example of herd mentality by Republicans fueled by partisan politics. Each member of the Florida delegation had to sign off for the House naming bill to be considered.

“To witness on the House floor, Republican votes change in disapproval of the bill during the final seconds of roll call,] was abhorrent,” Lawson said.

Florida Republican Rep. Gus Bilirakis’s office said he signed the House measure as a “professional courtesy” to Lawson but “no longer wished to proceed with the building name change” after learning of the ruling.

Not all of the Florida GOP members received the memo on the bill. Republican Rep. Kat Cammack reportedly called other offices to find out what was happening. She also opposed the measure.

Political pundits and legal eagles have slammed the House’s decision.

Retired Tallahassee Democrat capitol reporter Bill Cotterell covered some of Hatchett’s cases during his tenure. He said “partisan elected politicians shouldn’t judge judges.” They “have to make rulings on statutes and legal precedent, not what voters want,” he wrote in a recent op-ed.

“It’s not known how Hatchett might have felt, personally, about the school prayer case or any of the hundreds of other decisions he rendered on the state and federal courts, but no one ever accused him of not ethically following the law,”Cotterell wrote.

Baltimore attorney Eric Schuster, who completed a clerkship with Hatchett in the 1980s, said House GOP members’ actions reflect an “absence of simple human decency and a “total lack of respect” “for those who stood for justice.”

“He was unbelievably smart,” Schuster said of Hatchett. “But, more importantly, he was a pioneer, a man of the utmost integrity. That is why I am at a loss for words to understand the actions of the House Republicans.”