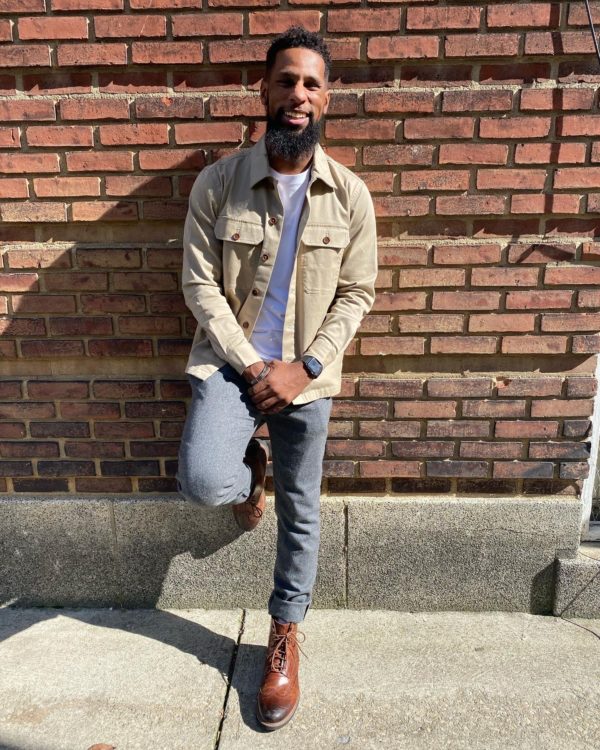

Philadelphia Man Becomes First Black Acceptant Into Groundbreaking Biotech Graduate Program at His University

Nafees Norris is on winter break.

The 26-year-old Philadelphia native just completed his first semester of graduate studies at Thomas Jefferson University.

But Norris is not just any student. And the Jefferson Institute of Bioprocessing (JIB) is not just any master’s course. The hybrid program opened in May 2019, becoming North America’s first specialized training institute for biopharmaceutical processing.

Norris became the first Black person accepted into the 12-month accelerated master’s program.

Biopharmaceutical processing is a rapidly expanding industry. Students in the JIB program learn gene therapy, protein replacement therapy and how to create vaccinations for pathogens such as COVID-19.

“I want kids from not only my city, but from other cities also, to realize you can get out of here without, you know, dribbling a ball or fiddling with a mic,” Norris told Atlanta Black Star. “You can actually use your head. I want people to believe that.”

Norris’ love affair with science began when he was 7. While studying plants in the first grade, he wanted a hands-on experience. He got just that when he saw a patch of weeds and dandelions growing in an empty lot near his home.

“I remember — I still have the cut on my fingers to this day — I put my finger on a weed,” he reminisced. “Most kids see blood and they start crying and they run home and try to get a Band-Aid. But me, I was so fascinated by it, I just thought deeper to what it really was. Like, how can I study this? That’s the moment I knew I was very interested in some type of science. I didn’t know what yet.”

Despite that interest, life pushed science to the back burner. Norris hails from North Philadelphia, a hardscrabble pocket of the City of Brotherly Love. The youngest of seven siblings, Norris grew up in a working-class household in a tough neighborhood where survival, not math and science, was held at a premium.

On top of that, Norris saw no Black scientists around him or any representations of them in movies or on televisions. He said it convinced him that becoming a scientist wasn’t a real-life option for him.

It wasn’t until Norris became homeless at 21 that he gravitated back toward what sparked his interest at an early age. Bouncing from couch to couch with -$21.79 in his bank account, Norris grew frustrated with his stakes in life. He applied to Community College of Philadelphia and used his last $187 McDonald’s paycheck to buy a cheap laptop so he could study for the placement test.

He got accepted and coaches recruited him to the school’s track team. They remembered him being an all-city track star at a local high school just a few years prior. When an academic adviser told him he had to declare a major, Norris asked what was the hardest major in the school. The adviser told him nursing and biology. Norris chose the latter.

He struggled out the gate, failing one of his early math classes, and got a C in biology. Norris was thinking about dropping the major because it was too hard. But then he met with his academic adviser, who told him “you’re not cut out for the sciences.” It was the motivation he needed to continue.

“I stood up and said, ‘Tell you what. I’m going to come back here in four years and I’m going to slap my degree on your desk. And it’s going to say biology.’ And I walked out and I’ve never seen her again.”

Meanwhile, his success on the track continued to attract attention. Norris had no intentions of attending a four-year college. But coaches at Neumann University saw his potential. He was dusting their runners in long distance sprints and relays. And in July 2016, Norris was recruited on a track scholarship to the private liberal arts school just outside of Philly.

But Norris continued to struggle academically. He failed four classes at Neumann and was placed on mandatory academic probation in the spring semester of his junior year.

“People thought I had this 4.0 and all this stuff,” Norris said. “I knew the stuff. I knew how to teach it. I just was a terrible test taker.”

Dr. William Herron, one of Norris’ chemistry teachers, helped him turn things around. The professor spent time tutoring Norris during his office hours.

He also made sure Norris stayed on top of his studies. If he caught him lollygagging in the halls, Herron would tell him to get to class.

“He said, ‘I am going to push you.’ And he pushed me like no other teacher has ever pushed me. Period,” Norris recalled.

Herron taught Norris through repetition. The professor had him solve chemistry equations over and over until Norris became quicker at working through them.

“What he did was he used what I knew to get me to understand what he was trying to teach me,” Norris said. “So he used the repetition of track and field because that’s what I was able to understand.”

Norris was required to find an internship in his field during his junior year in 2019. But the work studies are competitive, and Norris’ GPA put him at a disadvantage. He said he applied for more than 200 internships and got rejected by all of them. He faced the prospect of having to repeat a semester.

But Norris took his fate into his own hands. Just three days before his deadline to acquire an internship, Renold Capocasale, the founder & CEO of FlowMetric, Inc., a biotech company just outside of Philly, came to Neumann to speak.

Norris skipped an anatomy class, found an old, wrinkled suit, and attended the lecture. He waited until the floor was opened for questions, then made a bold move.

“I stood up and I grabbed the mic and in front of about like 150, 200 people,” he recalled. “And I asked this man for an internship. Straight up, right there. I looked him dead in his eye and said that.”

Capocasale said yes and Norris became FlowMetric’s first ever intern. He started working in the IT department, but after a few weeks he was assigned to help with lab work. That’s where he met Michael McGrane, a scientist who took Norris under his wing and taught him how to do navigate the lab.

Things were going well through the first few months of Norris’ senior year. His grades were up, he was doing well in his internship and cruising toward graduation.

Then the bottom fell out due to some struggles in his personal life. Norris found himself homeless again, living out of his car for several weeks in November 2019.

He continued to go to school and work his internship. But he slept in his car, kept all his clothes in the vehicle and showered at an L.A. Fitness.

“It was very, very tough,” Norris said. “And not only was it tough, it was just very depressing. But I still had to push. I was like I’ve got everything on the line [graduation] in May of 2020. I cannot afford to fail because my ultimate goal is to take care of my parents.”

Norris said he was buoyed by a Bible scripture someone gave him: Romans 8:28 (“And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to his purpose”). He also had the help of two teachers at Neumann who convinced the school to give him a free dorm on campus through winter break.

Providence intervened in Norris’ life again in January. He was helping a friend who was directing a play at a church in Glenside, Pennsylvania. Norris had agreed to be an extra in the play and was supposed to attend a dress rehearsal during the first weekend of the year.

But he was going through a break-up and wasn’t feeling in the right state of mind. The friend prayed with Norris and talked him into coming. She told him she felt he needed to be there.

She was right.

As soon as Norris walked into the building, he was greeted by the church’s pastor, who introduced him to Cameron Bardliving, the director of operations for the bioprocessing program at Thomas Jefferson University.

“I’m not gonna lie, before he even spoke two words out his mouth while shaking his hand, he was already my hero,” Norris said of Bardliving. “To see a Black man that not only is a scientist-engineer, but to see that this man has a Ph.D and he’s also a director of operations … I never had a visual of somebody doing this on the level that he’s doing it. So before he even said two words to me, I admired this person. I was in awe. I’m not a star-struck person, but I was star-struck that day.”

The feeling was mutual. Bardliving was interested in him because of his internship experience at FlowMetric. He told Norris about JIB program and the two connected on LinkedIn.

Norris admits he didn’t know what biopharmaceutical engineering was at the time, but Bardliving invited him to the lab. That’s where he met Dr. Parviz Shamlou and Geoff Toner, JIB’s director of curriculum. The lab tour quickly turned into an on-site interview.

Norris told them he didn’t think he had the GPA to get into the program. Bardliving told him they’d heard about his work ethic and resolve and wanted to give him a shot.

“When I first met Nafees, I saw someone who was very respectful, humble and driven,” Toner told the Philadelphia Tribune. “He’s a resilient guy who has overcome some obstacles in life. He’s also a very determined person. Nothing is going to stand in his way from achieving what he wants.”

Norris applied, and within two weeks he’d been accepted into the JIB program.

“They made me feel like I should be there” Norris said. “They made me feel like you’re welcome here. Because usually you walk into like a school and they’ll make you feel like you need them. They made me feel like I was needed and wanted.”

He plans to launch his own business next year, aiming to become a traveling scientific lab technician to assist smaller labs. And he’s developing his own scholarship, called the Rise Above Award, to help minority students pursuing STEM careers.

Norris’ ultimate life goal is to build a STEM school in Philadelphia.

“When you put God first and you really work hard at your craft, your dreams will never come true,” he said. “Something greater will.”

“It will never be about me. It’s about inspiring the next generation or the next person coming up,” he continued. “Everything that I do is based off of that. I don’t care about any attention. I don’t care about any publicity. If my story is going to help somebody else and save their life or push them closer to their dreams, then I’m all for it.”