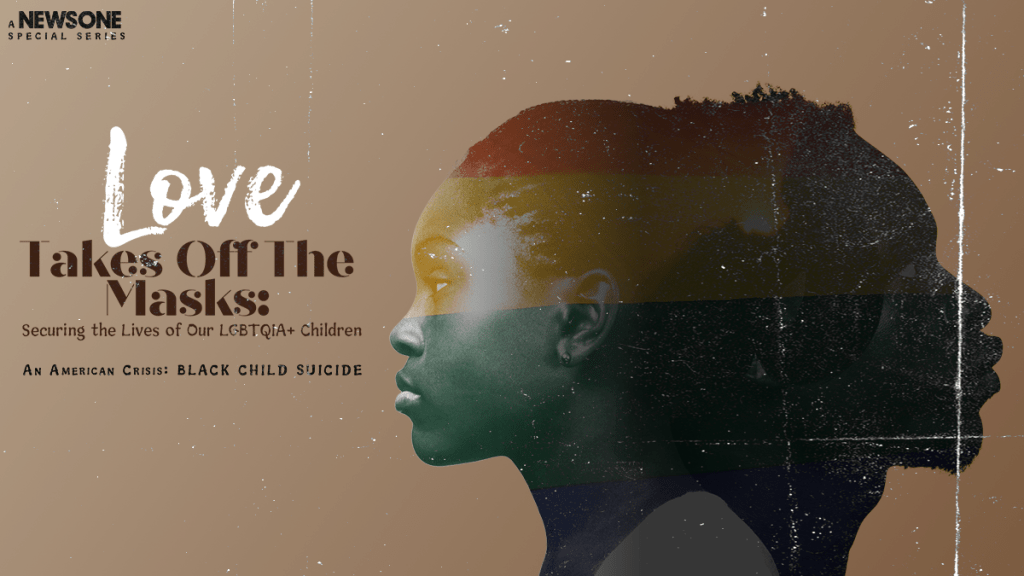

Love Takes Off The Masks: Our LQBTQIA+ Children Are Most At Risk Of Dying By Suicide. Elle Moxley Knows We Can Change That.

Source: iOne Digital Creative Services

The following article is the latest installation in NewsOne’s Special Series, An American Crisis: Black Child Suicide.

If you’re experiencing distress or need someone to talk to, you can dial 988 at any time for immediate support or the Trevor Project Hotline anytime at 1-866-488-7386. You can also text START to 678-678. Trained counselors are available to provide confidential support and assistance.

You are not alone.

Elle Moxley by Leah James

Years later, long after I’d attempted suicide in middle school, long after I’d found and embraced the joyous woman I knew I deserved to be, I had a conversation with Samaria Rice, Tamir Rice’s mother. I was an organizer by then, dedicated to ensuring that other Black Trans people like me were not only protected but provided loving guidance toward the certain knowledge that they had a right to live their full season of life. One of the most public expressions of that dedication came in 2015 when I helped plan and execute what became a historic gathering of the Movement for Black Lives in my home state, Ohio.

Samaria told me that when the news came on about the shooting she was at home making spaghetti. She knew that police shot Black children. She just never thought it would be her own Black child, Tamir, who was 12 and at the playground in November 2014 when police responded to a call that someone had a weapon. Tamir had a pellet gun. Within 3 seconds of their arrival, they’d shot that baby dead. But those words, I never thought it would be my child, resonated with me for the same reason they would resonate with anyone: I have empathy. But the words also resonated with me for a deeply personal reason: my mother had once used them to talk about me, her transgender baby. I never thought it would be my child.

I am dedicated to ensuring that Black Trans people like me know that we have a right to live a full season of life.

I grew up in Columbus, Ohio, with my mother and two sisters. We lived in a community of strong Black women who sustained themselves by sustaining and supporting each other. The ’90s of my childhood were completely unlike the ’90s they show in movies about us: that there was nothing except crack and guns and prisons early deaths. My ’90s were a beautiful expression of Black life. Neighbors knew neighbors and knew their children and we knew them and we played with them outside in front of our houses until the street lights came on. Back then no one talked about gender, what was “right” or what was “wrong.” We were actually allowed to just be people on this earth and I lived in that space, my long hair tied back in a ponytail. I presented sort of pretty tomboy-like, and no one picked on me or bullied me except my older sister. But even she wouldn’t let others bother me.

But that safety ended when I started school. The first sign was that my mother cut my hair right before my first day. She’d never done that before. She’d always let my hair grow as long as it could. I was too young to have any kind of big reaction to the haircut, but deep inside of me I sensed I was being forced to conform to a way of being that made no sense to me. But by far the hardest thing to endure then was the way my mother’s gentle love grew hard. I think she thought she needed to toughen me up as I was on the verge of venturing out into a world that I learned quickly didn’t welcome girls like me.

Queer children’s risk of death by suicide is four times higher than other children’s.

Elle Moxley by Irvin Rivera

Not that she would have identified me as a girl, but I always knew who I was and I think she did too. She wouldn’t say it or claim it, but without using the actual words, she telegraphed to me that I had to act like other kids or I was going to have a really hard time in school. She didn’t know how hard, though. And she didn’t know that suicide was the second leading cause of death for all children between the ages of 10 and 14, and that for LGBTQIA+ children, the risk was four times higher. I spent years being picked on and bullied. Years of fighting boys who were bigger than I was. Years feeling like an outcast, unseen, unwanted. And then one afternoon when I was 12 and convinced there was no way out of the hell I was living, I swallowed every pill I could find, praying I wouldn’t wake up.

Queer kids are at risk of death by suicide not because we’re Queer, but because of how we’re treated.

But I did and when I did, I knew that it was a message to me sent from God: I was supposed to be here, on this Earth, in this time. Suicide and suicidal ideation were not some kind of genetic code in my body because I was Queer. Early death was not my destiny. Queer kids weren’t at risk for suicide by virtue of our birth. The risk was higher for us because of the way we are treated in life. For Queer Black children that risk was higher because we were targeted for both our sexual and gender identities and because of our color and culture. We experienced an extra level of ostracization and rejection—often from places that were supposed to be safe for us. Like school. But by the time we’re just 14, more than half of us will have seriously considered or attempted suicide. Seventy percent of Black Queer children who are not Trans, experience harm related to bullying and discrimination–both causal factors in completed suicides. For Black Trans children, that percentage jumps to 83%.

Last year more than 500 anti-Trans/anti-Queer bills were introduced in state legislatures. As of this January, more than 285 new bills have been introduced.

As I grew older and became more and more determined to drive down those numbers, I began to speak out about the world we deserved, the love, peace and safety Black Trans people deserved. By the time the Black Lives Matter movement took hold, I was awash in all the feelings of power and hope that defined those first years. And of course it hurts to now see, just a few years later, how collective hate has, for the moment, taken the reins. Last year more than 500 anti-Trans/anti-Queer bills were introduced in state legislatures, three times what we’d seen in 2022. As of this January, more than 285 new bills have been introduced across the country. Since 2023, there are some 75 new hate bills in the U.S.

Most of those bills target education and healthcare—which is to say that at the very highest levels of American society, there is consensus that people like me should be erased from both the past and the present. Governors and legislators like Ron de Santis of Florida are determined to take us out of history, not even allowing the word “gay” to be spoken. And in an attempt to erase us from our present and future, there are threats to gender-affirming surgery. We won’t take that laying down. I won’t.

Because even in the face of these atrocities, I remain an Afro-futurist, which for me means that I believe in our collective power to make the tomorrow we need, absolutely possible. It means that inside myself, I live as though that tomorrow is already here. No one has the right to define me—or you. I am anchored to deep faith, a knowable faith that instructs that while I must never forget the child I once was who saw no options in life, I will neither give up on the woman who knows that there are. Even within the hells we’ve known there are pockets of hope. Our work is to embrace even just one piece of that hope, one person who brings that hope, and then nurture it until it reaches full blossom.

For me it was my literature teacher, Ms. Sowers. I was an awful student, not because I didn’t understand the work but because I was mad; trying to live was enough work for 10 people. Why were they making me do schoolwork too? Plus I was terrible at performing “boy.” But one day, Ms. Sowers pulled me aside after class. She told me her son was gay and then she played a song for me that she said had been helpful for him, “I Hope You Dance.” That song broke my heart and then it put it back together only more whole, more open. I could feel all the possibilities of the world, all the beauty. The slurs and brutal moments had far less space to grow. They began to shrink right then, in the moment I was finally, fully seen. Seen and loved as I was. It took just one woman. One song.

I’m a living example that our pain can be disrupted and we can live in joy.

I’ve lost so many friends in my life. And I know what I cannot prove: that some of those deaths were suicide and some of them were murders. In 2019, Nigel Shelby, a 15-year-old Queer boy from Huntsville, Alabama, in Madison County couldn’t see any way out of the bullying he was experiencing, the homophobic hate—even with a loving mother beside him. He’d asked for help from his school’s administration. They opted to do nothing. Opted to dismiss him. Nigel died by suicide April 18 of that year. And despite the expressions of grief and horror at what happened by many including well-knowns like Justin Bieber, the Alabama community that had created the killing field that Nigel could not survive on, continued to spread hate and harm.

Madison County Deputy, Jeff Graves, took to Facebook and wrote that “ Society cannot and should not accept this behavior….’Liberty, Guns, Bible, Trump and BBQ’ — that’s my kind of LGBTQ.” He was suspended from the department and then allowed to resign in May of that year. But he was also immediately hired in a nearby county who felt he “deserved a second chance,” a chance Trans folk don’t typically get. Even among those who are allied with us I still find people not really seeing us. Allies often see only our pain, not our power. But I’m a living example that pain can be disrupted. We can live in joy.

There’s been work done to tell the world we’re dying, but not nearly enough to say how or why, and there hasn’t been work done to document how and why people like me are living—joyously. There are magic powers in that kind of documentation. There are lifejackets, fresh air, holy manna in them.

There’s such a dearth of information about young, Queer, Black people, generally. Our deaths are rarely given full investigation because our lives are not. By their own admission, researchers for the longest period never tracked deaths by suicide for Black children, and even as they now have begun undertaking that work, they have to do what previously they have not: disaggregate childhood experiences by the broad landscape of gender and sexual identities. And they have to talk to survivors. I’m not the only one.

Black LGBTQIA+ children have not been considered in the research about suicide or about survival.

In 2019, I launched the Marsha P. Johnson Institute (MPJI) to defend, support and uplift the lives of Black Trans people. We needed our own platform for our own specific voices. There are places we share alignment with non-Trans Black people and with non-Black Trans people. But our experience as a whole is too specific to be meshed with others. It has its own history, its own curves, its own walk and breath. At MPJI we invest in our community, giving financial and other supports and resources to small organizations in the South and Midwest so that they are able to continue their advocacy work. We do likewise with artists whose work raises emotional awareness about our lives and about the threats to our lives that we can and must end.

There is magic power in learning how we can live joyously. We need to share it.

My work is to ensure that no Black Trans people are ever excluded from the right to feel and be safe. It’s to ensure we are all able to live long, happy lives as our fullest selves. It is to ensure that every Trans child knows how beautiful they are from the very beginning of their lives. That they have complete access to their dreams and the ability to realize them. That the sun meets them wherever they decide to go.

Elle Moxley is the founder of the Marsha P. Johnson Institute and Forever Free Productions. Ms. Moxely directed the short documentary film, “Black Beauty.”

RESOURCES

WATCH: Black Child Suicide: A Meditation For Survival With Dionne Monsanto

If you’re experiencing distress or need someone to talk to, you can dial 988 at any time for immediate support. Trained counselors are available to provide confidential support and assistance.

You are not alone.

Three Things You Can Do Right Now if You Feel Overwhelmed

Reach Out for Support: For young people, please immediately talk to a trusted adult about how you’re feeling. This could be a parent, guardian, teacher, school counselor, or another supportive adult in your life. For LBGTQIA+ young people, please call the 24/7 Trevor Project Hotline at 1-866-488-7386 or text START to 678-678.

Practice Self-Care: Listen to music you love. Take deep breaths. Meditate. Walk or jog or dance. These are aerobic exercises that help increase serotonin and can make you feel immediately better. If it’s a beautiful day and safe to go outside, go outside. Take in the fresh air. Look for small things that might make you smile. Journal. Listen to music. Do a hobby you enjoy. Drink water. You matter. We need you here.

Seek Professional Help: If feelings of overwhelm persist or become too much to handle, talk to one of the free counselors on one of the helplines. What free or low-cost mental health supports are available to you? Ask if they can recommend a Black therapist. There’s often greater synergy between people of similar backgrounds.

Additional National Hotlines

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: (800) 273-8255 available 24/7.

The Crisis Text Line – text TALK to 741-741, available 24/7

The Steve Fund text STEVE to 741741

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline – Text 988

Books and Films to Consider

All the Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson. A young-adult memoir that explores the author’s memories of being bullied to being loved by his grandmother, early sexual relationships and other trials and triumphs of Black Queer Boys. Age Range: Young adults and adults 13 and up.

Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More by Janet Mock. A powerful memoir about coming of age as a Black Trans woman and how she found home in herself. Age Range: Teenagers 16+ and adults.

Teen Mental Health and Suicide in Black Families. This PBS documentary explores the unique challenges and experiences surrounding teenagers’ mental health and depression and suicide within Black families. It offers insights and resources for support. Age Range: Teenagers 13+ and adults.

The post Love Takes Off The Masks: Our LQBTQIA+ Children Are Most At Risk Of Dying By Suicide. Elle Moxley Knows We Can Change That. appeared first on NewsOne.