Biden passed that torch slowly, hanging on until the wheels finally came off

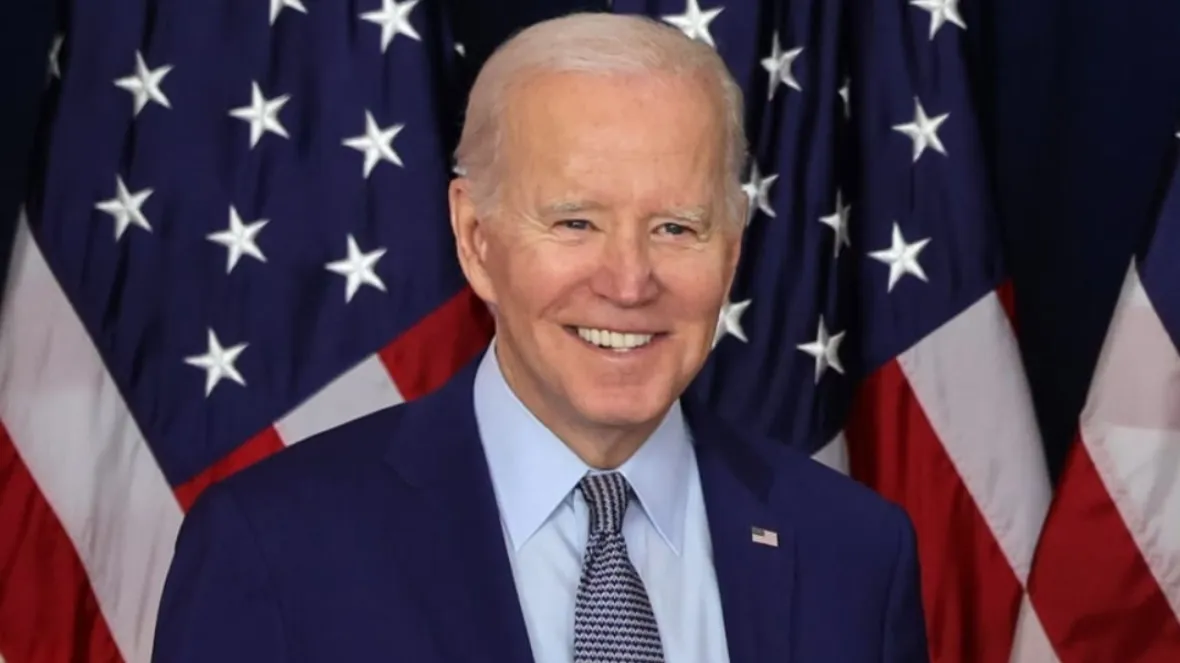

President Joe Biden arrives to deliver remarks at UNLV on March 15, 2023 in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo: Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

Publicly, President Joe Biden vowed he was all in for his 2024 reelection campaign to remain in the White House — until the day he got out.

WASHINGTON (AP) — As the “pass the torch” drumbeat thumped on from lawmakers wanting him to quit the race, President Joe Biden maintained a brave face. Publicly, he vowed he was all in, until the day he got out.

But there were telling indications he was listening to that beat long before he ended his campaign for reelection. One sign was over a week ago, when Chuck Schumer visited his Delaware beach house as an emissary of gloom.

The Senate majority leader had spoken with Barack Obama, Nancy Pelosi and the House Democratic leader, Hakeem Jeffries, a few days earlier. He had heard from nearly every Democratic senator, pinging him over the last three weeks on his old-school flip phone.

He wasn’t speaking for all of them, but for many.

Think about what’s bound to happen to Democrats in Congress, Schumer implored the president. Think about the generations-long impact of a Supreme Court with Donald Trump in the White House. Think about your legacy.

“I need a week,” Biden said. The two men hugged.

That scene and those words were described by someone familiar with the conversation, who would only detail it on condition of anonymity. Other firsthand observers of Biden’s struggle to stay viable also described a privately contemplative president during his days of decision.

Some spoke on the record; others anonymously. Together, their accounts show a president who was determined to exhaust every avenue to keep his hopes alive, but ultimately not in denial about the prospects.

By the weekend, if not sooner, the gravity of it all reached a critical mass — the terrible polls, the precipitous drop in big-money donations, the sad voices of those he most respected and had worked with for decades.

One insider said Biden “began to come to a decision on Saturday evening,” in the company of four close advisers. Things moved quickly Sunday. Biden gave South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn early word he would be stepping aside, in what the congressman called a “very pleasant conversation.” He did not speak with Pelosi at the time.

In a hooded Howard University sweatshirt, workout sweats and sneakers, Harris held several conversations with Biden and as the day wore on, spent over 10 hours on the phone with more than 100 politicians and some activists. She knew she would get the huge boost of Biden’s endorsement, yet needed to be seen as earning the nomination in her own right.

At 1:45 p.m., after separate calls to Harris, chief of staff Jeff Zients and campaign manager Jen O’Malley Dillon, he was connected on the phone with a small group of other advisers.

One minute later, with the release of his letter on X, the world knew.

Democrats had blanched in the first seconds of the June 27 debate with Trump. Low energy, hoarse, sometimes inaudible, Biden did not meet the moment as more than 50 million people watched.

Some outliers were left thinking the unthinkable — Biden had to go. But it was still possible for many to believe Biden merely had a “bad night,” if they gave him the benefit of the doubt.

More fumbles over the following days all fed into the public’s suspicion, simmering over several years, that Biden was not fit for another term. The loyalist insiders kept insisting Biden was on his game. The vast nation of non-political outsiders saw through the pretense.

Recommended Stories

But as questions about Biden’s acuity rolled into the first weekend after the debate, most lawmakers’ phones — including those of the top rungs of congressional leadership — remained silent from the one person who could quell the unease: the president himself.

Two days before the Fourth of July, Texas Democrat Rep. Lloyd Doggett, 77, became the first Democrat to call for Biden to withdraw from the race.

Pelosi, the former speaker, and Clyburn began openly airing their concerns about Biden’s condition, creating a permission structure for others to do the same. Early on, Pelosi said it was legitimate for Democrats to ask whether Biden’s night was a mere episode or a sign of a condition.

Soon, the list of lawmakers saying Biden should withdraw — or at least saying he had no chance of coming back against Trump — was growing.

They were playing a risky game with their careers — the party brass on one side, constituents on the other. No one wanted to cross the hunkered-down Biden campaign, but fears were rampant that the president’s continued candidacy would take down Democrats across the landscape in November.

The Biden-must-go contingent, though hugely outnumbered by fence-sitters and Biden loyalists, was not to be swayed easily. On several occasions, when the president made a good speech or showed sharpness off script, the list only grew.

Schumer eventually told Biden aides that he wanted them to hear from caucus members themselves and invited them to a meeting July 11.

That meeting did not go well. Almost no senators expressed confidence in the president. But even afterwards, Schumer was worried that the heavy concerns were not getting through to Biden.

Following the meeting, Schumer called Jeffries, Pelosi and Obama. He decided that day that he needed to see Biden.

They met that Saturday in Rehoboth, hours before the assassination attempt on Trump. Schumer told Biden he came out of love and affection, then gave him his bleak prognosis. Biden took the week he said he needed.

On the fateful Sunday, the Biden campaign was still pitching the line that their guy was full-on in. Aides pointed to a letter by Democratic Party chairs in seven swing states that urged Democrats to unite around Biden.

“We understand the anxiety,” said the chairs. “But the best antidote to political anxiety is taking action. You can’t wring your hands when you’re rolling up your sleeves.”

On the Sunday news shows, Sen. Joe Manchin the independent West Virginia senator who caucuses with Democrats, called on Biden to “pass the torch.”

On CBS, Biden campaign co-chair Cedric Richmond said flatly of the president: “He’s going to be the candidate.”

“He’s in a fighting mode,” Richmond added, “and I’m with him, and I’m gonna be with him until the wheels fall off.”

Which the wheels did.