A Stolen Legacy: California Beachfront Town Grapples with Seizure of Black-Owned Hotel In 1920s

An L.A. County official recently announced plans to possibly return a $75 million beachfront property to the family of a Black couple that once owned it.

The news comes 97 years after policymakers in Manhattan Beach wrested the property away from the family as part of a power move to oust Black people from the Southern California city.

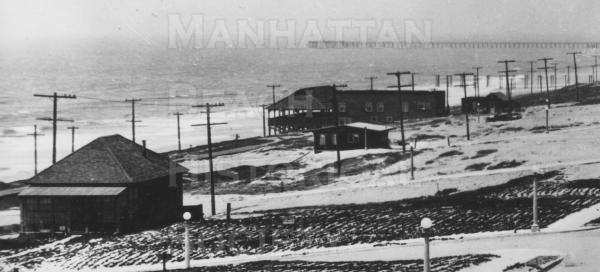

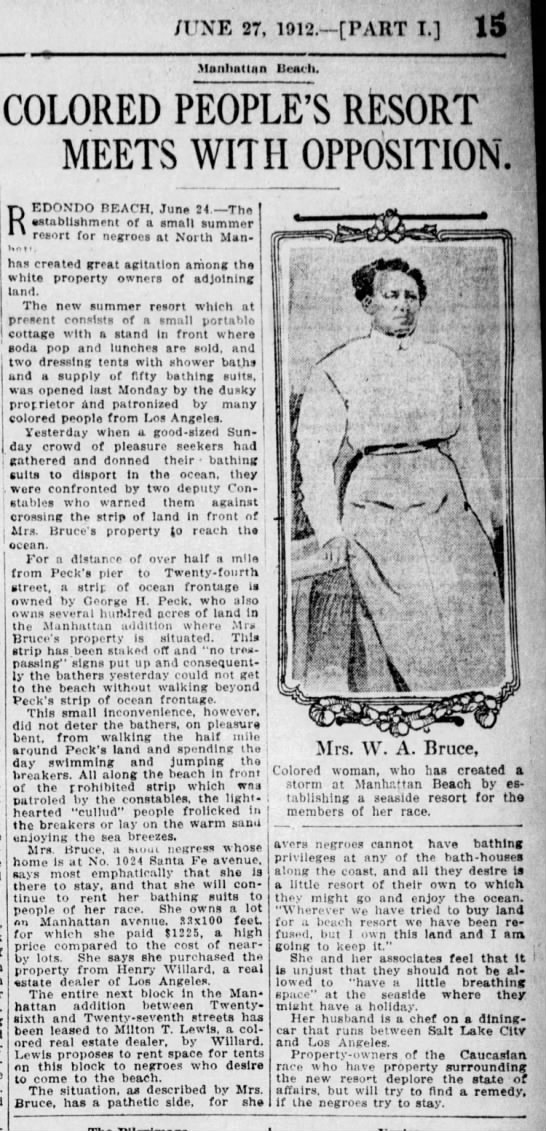

Charles and Willa Bruce were among the first landowners in the coastal town when they bought a patch of land on the shores for less than $2,000 in 1912.

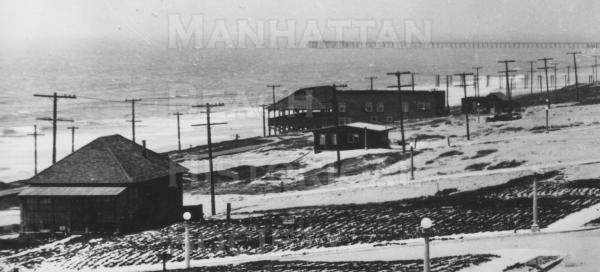

The couple built a beachfront resort named Bruce’s Lodge overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The popular hotel served as a scenic hideaway for Black travelers and attracted African-Americans to establish roots in Manhattan Beach.

It was the centerpiece of an area that came to be known as Bruce’s Beach. It was one of the few beaches in Southern California where Black people could hit the surf.

“They just didn’t want an influx of Black people, because the resort was starting to draw more blacks,” Duane Shepard Sr., a surviving relative of the Bruces (no relation to this reporter), explained in a phone interview with Atlanta Black Star on Tuesday.

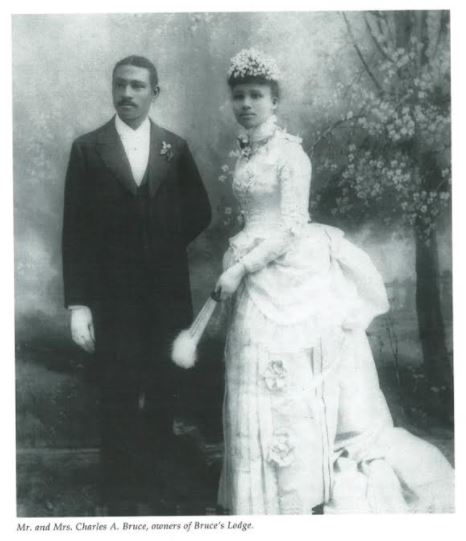

But it was the era of Jim Crow, and the prospect of a flourishing Black beach community was too much for other Manhattan Beach residents to stomach. By 1920, the Ku Klux Klan had begun targeting the resort, using violence to terrorize the Bruces, the beachgoers who visited their hotel, as well as other Black families that had built cottages for themselves.

Klan members made threatening phone calls and slashed tires. They burned crosses and even attempted to burn the resort down.

When those scare tactics didn’t drive Black residents out of town, the city took matters into their own hands. Manhattan Beach officials condemned the neighborhood and seized the Bruce family’s hotel property in 1924. They also seized property from about 24 other Black landowners through eminent domain, claiming the city needed the land to build a park.

Yet the land remained vacant for at least 30 years. And the city park was not built until the 1950s on a lot just east of the Bruces’ hotel property.

Kavon Ward, an advocate activist who lives in Manhattan Beach, has for months led a crusade to get the family restitution. She’s also calling on the city to pay out reparations to all Black people possibly, saying Manhattan Beach’s actions in 1924 shifted generational wealth.

Ward proposes the more widespread reparations could come in the form of home loans with zero-interest rates that would make it more affordable for African-American families to move back into a city that currently has less than a 1 percent Black population.

“Most of the families out here in Manhattan Beach, they are able to pass down that property to the next generations,” Ward said. “They probably bought plots of land for $1,000, and now they’re worth $10 million or $20 million. But that’s because they were able to pass it down and the Bruces didn’t have that opportunity.”

Now L.A. County owns the beachfront property. County Supervisor Janice Hahn said she was shocked to learn about the racial history of the property, which now serves as a hub and training center for the county’s lifeguards. Last week, she confirmed to ABC 7 in Los Angeles that she is contemplating options to recompense the Bruce family for their stolen land. That includes the possibility of returning the property to the couple’s living descendants.

“I’m considering, first of all, giving the property back to the Bruce family,” Hahn told the TV station. “I wanted the county of Los Angeles to be a part of righting this terrible wrong.”

Other options include turning ownership of the property to the Bruce descendants and leasing it so the county can continue using it as its lifeguard headquarters. The county is also considering the prospect of paying the family restitution.

After being kicked off their land, Charles and Willa Bruce joined the other Black families in suing the city, alleging racial prejudice was the real reason their properties were seized. The Bruces sought $120,000 in compensation. But after years of litigation all the Bruces were awarded was a $14,500 payout.

“There are tuitions that haven’t been paid, homes that haven’t been bought, businesses that have not been started,” Shepard said. “We went from being rich basically, an enterprising family, to absolutely nothing.”

Manhattan Beach is in southwestern Los Angeles County, less than 20 miles south of Santa Monica. The Bruce family’s hotel sat on a prime piece of real estate that straddles the sand line. Officials estimate it’s worth $75 million today.

Shepard has been researching his relatives’ history for years and trying to spread the story of what happened to them. Charles and Willa only lived 10 to 11 years after their land was seized, according to him. They spent much of their remaining years living in poverty and working as cooks in a diner, when they were once owners of their own dining hall.

“They took our business, our land, our livelihood, and our legacy,” Shepard said. “They had to move from Manhattan Beach and live in abject terror of being murdered by the Ku Klux Klan or the police department there.”

Shepard wants to ensure the property’s ownership will be rightfully restored back to the family. He also is demanding restitution for 96-plus years of lost revenues and punitive damages from the Manhattan Beach Police Department and city council “for their collusion with the Ku Klux Klan in terrorizing our family.

“The lives and the emotional distress, we can’t get that back or get that corrected,” Shepard added. “But we can make the family whole by helping with the future, our young people that are going forward, helping them to get a foothold in America.”

The city of Manhattan Beach created a special task force last year commissioned to find penances for the city’s sins of a century past. The advisory group held its last meeting Wednesday, March 3, before presenting its final recommendations to City Council members. The task force recommended the city issue a public apology, create an art exhibit and correct historical inaccuracies on a plaque at Bruce’s Beach that tells the story of the area.

Both Shepard and Ward scoffed at Manhattan Beach’s efforts and criticized officials for not working with the family to find solutions. They agreed the city appears interested in symbolic gestures, as opposed to substantive measures.

Shepard said the family has never been concerned with a public apology from the city. But Ward said that is a key peice of the puzzle.

“We believe that it is significant for them to state in public that they were complicit and that it was their fault,” she said. “I think that’s important in trying to get the restitution the family is asking for. They have to admit guilt. And when you admit guilt, people are going to say, what are you going to do about it? How are you going to remedy it?”