As the Second Black Mayor In New York City’s History, Eric Adams Is Quickly Earning Another Title As the Most Disliked Mayor In America

New York City Mayor Eric Adams tends to make headlines for his agendas and remarks addressing several hot-button social issues that disproportionately impact marginalized communities.

Combining that with the fact that he’s the mayor of the most densely populated city in America with one of the largest populations of Black Americans means that his initiatives can set precedents and examples for other big-city mayors. And more often than not, his national news features often cover more of his contentious and questionable takes on several socioeconomic affairs.

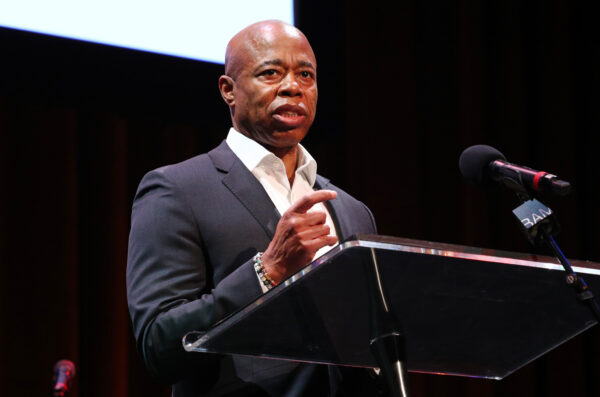

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – JANUARY 17: New York City Mayor Eric Adams speaks onstage at the 36th Annual Brooklyn Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at Brooklyn Academy of Music on January 17, 2022 in New York City. (Photo by Astrid Stawiarz/Getty Images for Brooklyn Academy of Music )

A Siena College Research revealed that only 29 percent of Black voters show approval for Adams, while 50 percent held an unfavorable view of him. Adams was elected the 110th mayor of New York City in 2021, making him the second Black mayor in the city’s history. David Dinkins was the first, serving from 1990 to 1993.

As a retired New York Police Department captain after serving on the force for more than 20 years, Adams ran much of his campaign on a broad, tough-on-crime platform, pledging to reform the NYPD due to concerns over a rise in violent crime. His message landed with working-class Democratic voters and those in liberal areas of Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Trending Today:

How Black Folks Really Feel About the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

It’s also not his first stint in public office. The 63-year-old served in the New York State Senate from 2006 to 2013 after retiring from the NYPD. Then, he became the Brooklyn borough’s first Black president.

In his transition to mayoral office, Adams inherited a weighty set of circumstances. He had to contend with the citywide health and economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, a nationwide reckoning on police brutality, and pinpoint ways to reduce violent crime in the city, which rose during the pandemic. It would be a challenge to meet citizens’ demands for reform while also sticking to his own police reform agenda.

Unlike his predecessor, former Mayor Bill de Blasio, Adams wasn’t averse to the stop-and-frisk tactic that is often employed excessively among citizens in marginalized communities. However, what he sought was to neutralize abusive uses of the tactic.

“If you have a police department where you’re saying you can’t stop and question, that is not a responsible form of policing,” Adams said of the tactic.

His approaches to police reform were at odds with many Black Lives Matter (BLM) organizers and demonstrators in the city. For instance, he restored the anti-crime units that were connected to the deaths of Eric Garner, Sean Bell and Amadou Diallo. Citizens complained for years that these units — which included officers dressed in plainclothes — abused the city’s stop-and-frisk policy.

Hank Newsome, co-founder of BLM of Greater New York, was even labeled a domestic terrorist by NYPD officials for warning Adams that riots and “bloodshed” would ensue if he revived the units.

In 2022, he publicly stood by officers who lied about the details of the violent arrest of a Bronx teen in possession of an illegal gun. Video footage showed 16-year-old Camrin “C-Blu” Williams with his hands up when police grabbed the teen’s sides and the gun went off in his pocket, injuring both Williams and another officer. Even though a judge said those officers had no grounds to search or detain Williams, Adams said they shouldn’t be “demonized” for their actions.

“I don’t believe those officers broke the law,” Adams said. “I think those officers were aware from a previous arrest of that young man, and there are steps to take to ensure you protect yourself and protect the public.”

Adams was also criticized for his response to the death of Jordan Neely, a homeless man who was choked to death by Daniel Penny after reportedly undergoing a mental health crisis. Neely’s death made national news and incited public outcry for Penny to be charged with murder. Neely was a well-known Michael Jackson impersonator and subway performer who also had a history of confrontations in the subway, including an instance in which he attacked a 67-year-old woman.

Adams, however, shied away from using the term “murder” and encouraged people to wait for the results of the police investigation. Those remarks were denounced by Neely’s family and lawmakers like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who believed the mayor should have offered stronger sympathy and condemnation over the death.

Adding fuel to the fire, Adams also used Neely’s death to point to what he believes is a need to forcefully hospitalize mentally ill people who are unable to meet their own needs, a procedure that many oppose. The New York Civil Liberties Union responded that the practice plays “fast and loose” with people’s legal rights, but Adams sees it as a necessary intervention to combat both homelessness and mental health crises. California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law last year authorizing forced treatment for mentally ill, unhoused people.

Although that push drew massive public blowback, Adams just recently announced a new agenda to expand services for people living on the streets of New York City with severe mental illnesses who don’t have access to treatment and care. That plan includes deploying medical professionals rather than police officers to 911 calls for people in crisis and creating centers of community for people who often suffer in isolation to connect them with jobs and educational opportunities.

However, that agenda follows one of Adams’ most unpopular efforts by far that he executed in his first few months as mayor — the removal of hundreds of homeless encampments to offset the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Without providing any details on where or if any of these unhoused people would be relocated, Adams deployed teams to clear more than 200 homeless enclaves, angering many New Yorkers and drawing criticism that he was criminalizing poverty. This initiative inordinately affects communities of color. It followed a fairly new strategy launched by New York Gov. Kathy Hochul to prevent unhoused people from sleeping on subway cars.

He also recently announced an effort to try to stymie the migrant crisis in the city by launching a policy to stop sheltering single adult asylum-seekers, which could send thousands of people into the streets without housing or care.

New York City’s shelter mandate promises to provide shelter to anyone in need. Adams’ decision was made to pause the guarantee for the time being. More than 100,000 migrants have arrived in the city since 2022 and more than 60,000 are in the city’s care.

The public’s opinion of Adams’ handling of the situation faced disapproval from 47 percent of respondents to a Siena College Research Institute poll, while only 31 percent expressed their support.

In stark contrast, Black voters across the state showed strong support for the moderate Democratic mayor in June, with a substantial 59 percent approving of him compared to 16 percent who disapproved in the mid-May survey.

Still, Adams’ time in office so far hasn’t been met with much public support from Black and Brown communities, and he has come down hard on critics who have deemed his administration racially biased, but we’ll see what he does with his last two years in office.