Some Therapists Claim an Increasing Number of Black Americans Have Sought Therapy Following ‘Shared Trauma’ of George Floyd’s Death

An anecdotal sampling of therapists around the country by The New York Times recently found that more Black Americans sought mental health services following the police killing of George Floyd in May of last year.

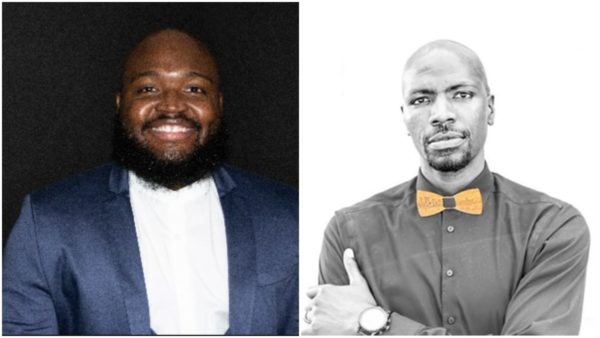

Dr. Douglas E. Lewis Jr., a Black clinical and forensic psychologist in the Atlanta suburb of Decatur said Black people experienced “shared trauma” in the aftermath of the highly publicized death that sent shock waves across the nation.

“I think people are starting to see therapy for exactly what it’s always been, which is more of an insight, building, more of an opportunity to see things in a different perspective, reframing,” Lewis told The New York Times. “It’s something that everyone could benefit from, not just people who may be diagnosed with a severe persistent mental illness.”

According to the American Psychiatric Association, Black people are less likely to receive the mental health services they need. Although mental health issues occur at similar rates among whites and Blacks, Black Americans are more likely to receive poor quality care and often lack access to culturally-competent services.

In 2015, just 5 percent of psychologists were Black, while only about 2 percent of psychiatrists are Black, although Black people make up about 13 percent of the population.

Jamil Stamschror-Lott, a Black therapist, and his wife Sara, also a therapist, are the founders of of Creative Kuponya, a mental health practice in Minneapolis, not far from where George Floyd died. They say the number of Black clients has gone “through the roof” since his death.

“We’ve seen everything that the nation has seen from afar, from folks in civil unrest and devastation, despair,” said Jamil Stamschror-Lott.

The practice focuses on community mental health and about 31 percent of its clients are Black.

A 2018 study found that a police killing of an unarmed Black person triggered days of poor mental health for Black people living in that state over the following three months. According to lead author David R. Williams, the accumulation of painful days was equivalent to what’s experienced by diabetics after a year.

Paul Bashea Williams, a black clinical therapist, spoke to CNN last month and offered several ways for Black people to care for their mental health after an unprecedented year and amid continued struggles against the pandemic and racial injustice.

“There is a difference between being informed and getting retraumatized,” Williams tells his patients. “Sometimes you are visualizing you,” he said, at a time when images and videos of Floyd’s death were being broadcasted daily on television and social media as the Derek Chauvin trial continued. About 90 percent of his clients at Hearts in Mind Counseling in Prince George’s County, Maryland, are Black.

Williams encourages Black Americans to acknowledge their feelings about incidences of police brutality and to be intentional about seeking community grounded in trusting relationships. Finally, Williams said it’s important to set boundaries and seek help.

“It is important for the Black community to get into therapy,” he explained.