Harvard and White America’s Creepy Obsession with Hoarding Black Remains

White America has always been a nation of serial killers.

The hair, scalps, ears, skulls, fingers, toes, skin, genitals, and photographs of its Black and Indigenous victims have been hoarded in private basements and attics, archives, and museums, and passed down like heirlooms of racial violence for centuries. After 175 years, Harvard University finally gave up photos of enslaved people they clung to like necrophiliacs with a fetish for Black death.

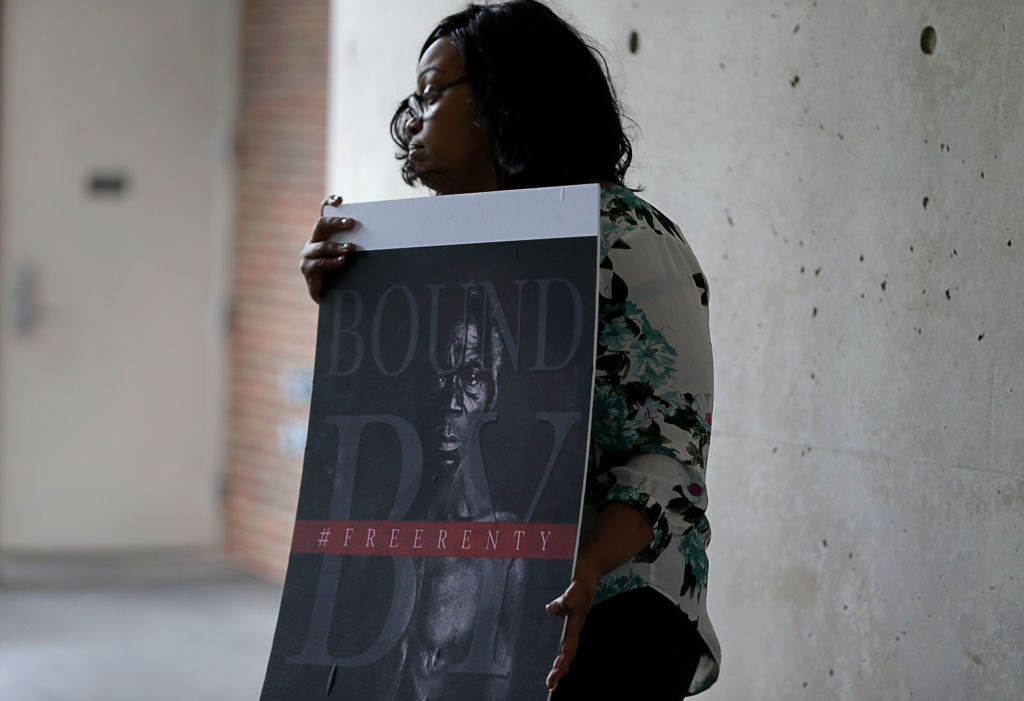

News came earlier this week that Harvard has finally stopped fighting to hold onto photographs of Renty and Delia, a father and daughter stripped naked in front of a camera by Louis Agassiz, a 19th-century racist biologist who used their images to peddle his theories of Black inferiority to justify slavery. For 175 years, Harvard treated these photos that were taken to dehumanize and degrade as its property, circulating and republishing them for a fee, even as the university praised itself for studying its own ties to slavery.

It wasn’t until Tamara Lanier, Renty and Delia’s great-great-great-granddaughter, sued in 2019, and the university faced pressure from faculty and students, that Harvard was forced to confront this sickness of its hypocrisy.

The university argued that the descendants had no rightful claim to the images. Never mind that the enslaved people in them were forced by their “owner” to strip naked, paraded in front of a room full of white people, and subjected to a degrading photo session that they never consented to.

These ancestors were captives whose bodies were stolen in life and their sexualized images stolen in death, yet Harvard fought tooth and nail to keep them like prized pornographic possessions, exposing the moral rot at the heart of elite universities still hoarding Black and Indigenous remains in their archives and museums, like the Peabody, where these photos were stored.

Harvard isn’t alone. The sickness runs deep across the Ivies and beyond. Yale, Princeton, Brown, Dartmouth, Penn, Johns Hopkins, Washington and Lee, William and Mary, and Rutgers all have documented ties to slavery. Some were established directly from the profits of human bondage. Some openly held slaves and advertised them for sale. At some schools, students brought their own enslaved “servants” to campus to cook their meals, clean their rooms, and entertain them while being subjected to routine abuse.

Black bodies were not just laborers, but exploitable subjects used for medical experiments, anatomical dissection, and racial studies seeking to “prove” racial inferiority. And even when researchers aimed to challenge racist ideas, they did so by treating Black bodies as specimens. For example, Johns Hopkins University historian Martha Jones was brought to tears when she found a lock of her own grandmother’s hair in Harvard’s Peabody Museum. Caroline Bond Day, a pioneering Black woman anthropologist in the early 20th century, had collected her hair for her study of Negro-White families in the United States. Her aim was to debunk prevailing myths about “mulatto degeneracy” and her work involved using popular race science techniques including measuring skulls, calculating “blood quantum,” and collecting hair samples which were pressed between plates of glass and filed away like botanical specimens.

While Day’s intentions were to refute racist pseudoscience, the methods she employed, which were rooted in the very frameworks she sought to dismantle, underscore the pervasive violence and insidious nature of race science in America. Jones’s discovery is a complex and haunting reminder of how Black bodies were often subjected to invasive surveillance and scrutiny, even in consensual efforts to affirm their humanity.

This violence wasn’t limited to Harvard and other universities.

Individual doctors, public health officials, hospitals, entire federal agencies, including the U.S. Sanitary Commission, the American Freedman’s Inquiry Commission, the U.S. Medical Museum, the Smithsonian, and the U.S. Surgeon General’s office systematically collected, measured, and displayed Black bodies to build a pseudoscience of racial inferiority.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission, working alongside racist figures like Frederick Law Olmsted, used Black soldiers in the U.S. Colored Troops as raw material for data collection, measuring and weighing them to support racist theories of Black physical and mental inferiority. These same federal institutions ignored evidence that contradicted their racist assumptions, instead characterizing Black people as disease carriers, their bodies as infertile, and their lives as expendable, all to justify limiting Black migration, withholding support, and ensuring a future of poverty, exploitation, and death.

These studies didn’t just shape racist science, they shaped federal policy, medical practices, and the everyday neglect, abuse, and death of Black patients for generations. The robust grave-robbing trade in Washington, D.C., fueled by the demands of Georgetown and George Washington University medical schools, turned Black cemeteries into supply chains for anatomy labs, where Black bodies were dissected, measured, and displayed without consent.

This sickness isn’t just a relic of the past.

The very institutions that profited from this violence — like Harvard, the Smithsonian, Penn, Yale, and others — still hoard the remains of Black and Indigenous people to this day. Harvard clung to those photos of Renty and Delia for 175 years because these institutions are built on the idea that Black bodies are objects to own, study, and display.

The Smithsonian still holds more than 30,000 human remains in its collections, including thousands of Black and Indigenous ancestors. Last year, the Associated Press and other outlets reported that the University of Pennsylvania stored the bones of a Black child killed in the 1985 MOVE bombing in a museum collection, like an exhibit piece, without consent, without dignity. These institutions hold onto these remains because returning them to their families and communities to be laid to rest with dignity would mean admitting the full scope of their crimes. It would mean relinquishing power, shattering the illusion of scientific objectivity, and confronting the ugly truth: that for centuries, America’s most prestigious institutions have built their prestige by treating Black death as a resource, and Black bodies as trophies.

But this grotesque hoarding of Black bodies didn’t start in America. The dehumanization and collection of Black and Indigenous people in the U.S. isn’t some isolated, uniquely American cruelty. It’s the continuation and perfection of European traditions that long treated human beings as raw material for spectacle, control, and study.

Long before this violence was racialized and systematized in the Americas, Europe had already laid the blueprint. For centuries, European authorities flayed the skin of the condemned, using it to bind books, craft shoes, and create other macabre artifacts. Public executions weren’t just punishments; they were performances, where huge crowds gathered as doctors and scientists eagerly dissected the freshly hanged and beheaded, turning human bodies into teaching tools. Skeletons of the executed were cleaned, wired together, and displayed in medical classrooms as anatomical specimens for generations, while the state sent a clear message about whose bodies could be mutilated, studied, and consumed.

This is the foundation of Western knowledge systems. Institutions like Harvard, the Smithsonian, Penn, and others didn’t just wake up one day and decide to hoard Black bodies. They inherited a centuries-old cultural script that normalized turning human suffering into property, data, and spectacle. What we call “knowledge production” has always been built on domination and the idea that some bodies, especially Black and Indigenous bodies, are disposable, exploitable, and worthy only as objects of study.

The ancient Egyptians—Africans, by the way—were practicing medicine, studying anatomy, and documenting treatments over 5,000 years ago, while Europe was still wallowing in its own filth, bleeding patients to death with no concept of sanitation, anatomy, or science. When European doctors and medical students finally began studying the human body, they were cracking open Black and Indigenous skulls, stealing bodies from graves, dissecting enslaved people alive, and displaying their remains in so-called scientific exhibitions. They didn’t just seek knowledge, they built an empire by stealing, dissecting, and hoarding the bodies of colonized people for profit, study, and display, all while calling it “progress.”

This is the ghoulish legacy white America inherited, perfected, and institutionalized in places like Harvard, the Smithsonian, and the freak show cabinets of 19th-century Europe. When white America began robbing Black graves, boiling bones, cataloging hair, and skin, and photographing the naked bodies of the enslaved, they were extending this long, morbid legacy into the brutal machinery of white supremacist science.

Even in the 20th century, the obsession with racial difference continued under the guise of scientific inquiry. At Johns Hopkins University, for example, embryologists collected over 3,000 human embryos and fetuses. Doctors harvested this “clinical material” from miscarriages and abortions, including scalps and genitals of unborn Black children, hoping to solve a trans-Atlantic debate over when Black people “developed” skin color. In the warped logic of race science, Black life, even in utero, was a problem to be measured, dissected, and solved.

This is the inheritance that institutions like Harvard, the Smithsonian, Penn, and others are clinging to when they hoard Black and Indigenous remains. This pathology has been cultivated over centuries. And this is why the fight for reparations, repatriation, and the righting of historical wrongs is so urgent. It’s not just about a few photos at Harvard or a few bones in the Smithsonian. It’s about dismantling an entire system that has treated Black life as raw material for centuries.

This isn’t just a story about Harvard. It’s a story about the entire Western project of how human bodies, especially Black and Indigenous bodies, have been the foundation for wealth, knowledge, and power in the West.

Some people are speculating that Harvard’s decision to finally relinquish these photos is a strategic move tied to its ongoing war with the Trump administration. But I don’t think so. This case has been dragging on since 2019, long before the latest wave of political attacks. Harvard didn’t suddenly discover a moral conscience because of Trump; they gave up the photos because they had to. They were backed into a corner by years of bad press, public pressure, and a lawsuit that exposed their hypocrisy. This is about Harvard’s long history of hoarding Black bodies, not a sudden act of resistance. Let’s not give them credit for doing the bare minimum after 175 years.

Harvard’s long-overdue surrender of the photos of enslaved people isn’t happening in a vacuum. It comes at a time when the Trump administration is waging a full-scale assault on archives, libraries, and the people who safeguard our collective memory. The recent firings of key figures like Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and Archivist of the United States Colleen Shogan, coupled with the dismantling of the Institute of Museum and Library Services, signal a concerted effort to undermine the custodians of our nation’s history. These moves aren’t just about bureaucratic reshuffling, they represent a deliberate attempt to control narratives and suppress inconvenient truths.

The mass deletion of government web pages and datasets, particularly those related to diversity, equity, and inclusion, further underscores this agenda. By erasing digital records and sidelining professionals committed to preserving historical integrity, the administration is effectively rewriting history in real-time. It’s a modern-day book burning, executed with the click of a mouse.

Could it be that these actions are not just about ideological control but also about destroying evidence? When institutions are stripped of their leadership, funding is slashed, and archives are purged, it raises the unsettling possibility that the fascist goal is not just to suppress dissent but to obliterate the very records that hold power accountable. In this light, the fight over Renty and Delia’s photos isn’t just about the past. It’s a warning about the future of historical memory in America.

While Harvard’s surrender wasn’t a direct response to the Trump administration’s attack on knowledge institutions, it’s all part of the same white supremacist playbook: hoard the evidence of your crimes, erase the inconvenient truths, and cling to the power that comes from controlling the narrative. Whether it’s Harvard fighting to keep stolen photos or the federal government gutting archives, the goal is the same: to protect the machinery of white power by suppressing the full, brutal story of Black life and death in this country.

SEE ALSO:

Why White Folks Are Grieving Over Destroyed Relics To White Supremacy

White Folks Gave Us ‘Black Fatigue,’ Now They’re Trying to Steal It